Father Bonaventura Ubach (Barcelona, 1879, Montserrat, 1960) entered the monastery of Montserrat in 1894 and was ordained a priest in 1902, together with the one who would later become the abbot of Montserrat, Father Antoni M. Marcet.

From an early age, he showed a keen interest in Bible study, which led him to work hard on learning Greek and Hebrew. After completing his first cycle of studies, he began teaching biblical subjects and Oriental languages in Montserrat.

From an early age, he showed a keen interest in Bible study, which led him to work hard on learning Greek and Hebrew. After completing his first cycle of studies, he began teaching biblical subjects and Oriental languages in Montserrat.

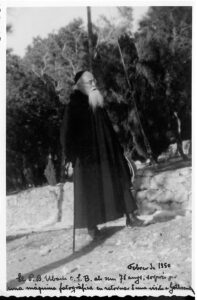

Seduced by the Middle East, based on his research as a biblical scholar, he began his travels to get to know the world of the Ancient Orient. He visited the biblical lands and began to collect archaeological pieces for the future biblical Museum of Montserrat. At the École Biblique de Jérusalem he was a disciple of the exegetes Lagrange, Vincent and Abel.

His first trip to Jerusalem was in 1906, and he studied and taught there until 1910. He had a special interest in “gaining experimental knowledge of the biblical country, and therefore travelling in all directions in Bible-related regions.” as his biographer, Fr. Romuald Díaz, says.

His first trip to Jerusalem was in 1906, and he studied and taught there until 1910. He had a special interest in “gaining experimental knowledge of the biblical country, and therefore travelling in all directions in Bible-related regions.” as his biographer, Fr. Romuald Díaz, says.

As a result of this knowledge, he published a series of articles in the Montserratina Magazine and the narration of his trip to El Sinaí (1913, expanded in 1951).

In 1913-22 he taught Hebrew and Syriac in Rome at the Pontifical Istituto Anselmiano. He took part (1917) in the preparations for the creation of the Eastern Congregation and the Pontifical Istituto Orientale, where he taught Syriac and Hebrew (1918-20). During this time did he publish the Hebrew grammar Legisne Toram? (1919), which was adopted in many seminaries and universities and republished several times.

Back in the East in 1922, he had a very close connection with the Syrian Catholic Church and collaborated with Patriarch Efrem Rahmani in the editing of Syrian liturgical books. His trip to Mesopotamia (1922-23) was described in the Diary of a Journey through the Regions of Iraq, which was published in 2010 under the title Diary of a Journey through the Regions of Iraq. (1922-1923).

For centuries, the Catholic Church only allowed the clergy to read the Bible and only in Latin. When this changed, in the 19th century, the only Catalan translations available were those of the Protestants, but their circulation was very limited outside that community.

Several projects tried to promote a Catalan version of the Bible, including the initiative promoted by Francesc Cambó, on behalf of the Fundació Sant Damas, in Barcelona (Fundació Bíblica Catalana).

Ubach, was one of the initial collaborators but ended up abandoning the project in disagreement with editorial criteria that prioritized the speed and literary quality of the translation over fidelity to the original text.

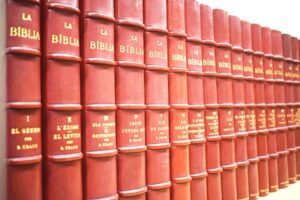

Far from giving up the project, the Abbey of Montserrat undertook its own translation of the Bible, characterized by philological rigour, the abundance of the critical apparatus and an exuberant photographic illustration. Between 1926 and 1954, twenty-five volumes of text and three other volumes of images were published, making the Great Bible the most exhaustive translation ever made in Catalan, and which was the basis of the popular Bible of Montserrat published in 1970.

Fr. Ubach published the following volumes of the great Bible of Montserrat:

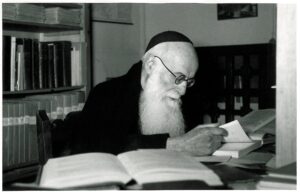

Returning permanently to Montserrat in 1951, he continued his biblical work and created a small study center of the Syriac Church; in 1952 he published Litúrgia siríaca de Sant Jaume. Anàfora dels XII Apòstols, version of the Syriac Mass he himself celebrated.

The Bible of Montserrat was, indeed, a pioneering and recognized work, but at the same time another important event took place for the Benedictine monastery. And it is that in the different trips that made by the Middle East, the P. Ubach in Ubach began to collect archaeological materials already from his first stay in Jerusalem, at the beginning of century XX. When he returned to Montserrat in 1910, he started the first nucleus of the Museum of the Biblical Orient in a small room of the abbey’s inn, which grew and evolved over the years until in 1962 it was divided into four current sections of the institution’s archaeological fund: Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Holy Land and Cyprus. His work meant the first solid school of ancient Orientalism in Catalonia.

Despite the remoteness and inaccessibility, the scenarios of the Bible have enjoyed a constant and central presence in the construction of the Western collective imagination, forming true mythical geography made of plastic and literary images that are not always accurate and, most of the time, just fictitious.

The opening of these territories to foreign travellers coincided with the invention of photography, and the first snapshots of the Holy Land (1841) had a huge impact on the European and North American public.

Those of the first photographers were a retrospective look, more attentive to the vestiges of the past than to the reality around them. A look that “biblicized” people and scenes, stripping them of their contemporaneity and making simple echoes of a distant time.

This view only began to change when the prospect of Western powers taking control of those countries opened up. From then on, rigorous knowledge of the territory and the precise categorization of the new subjects of the colonial administration were imposed.

Bonaventura Ubach life was nourished by a passion to gain a better understanding of biblical texts and share them. Driven by this desire, he soon left Montserrat to travel the roads of the Orient in search of echoes of those exceptional stories.

Despite having a great command of the languages of the Bible – Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek -, as well as Arabic and Syriac, he felt linguistic excellence was not enough and that the scriptures, removed from their context, lose a great deal of their richness. This is why he strove to acquire detailed knowledge of the landscapes, tangible remains and traditions of the peoples who had witnessed the birth of the biblical texts. On his voyages of discovery, Ubach always used the camera because he understood the communicative power of the image but also because he was aware that the world he was captured in his photographs was on the verge of disappearing, swept away by the emergence of modern times and its conflicts.

Since the death of Fr. Ubach in 1960, the photographic collection has been guarded by the Scriptorium Biblicum et Orientale of the Abbey of Montserrat, directed by Fr. Pius Tragan, who was a direct disciple of Fr. Ubach.

The photographic archive collection is made up of about 7,000 negatives, supported on plastic bases, mainly cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate. There are also some 600 glass plates and a set of maps and reference notebooks where there are lists of the places where the numbered and described photographs were recorded.

This photographic collection is unique in Catalonia and Spain, which, due to the current political situation of the Biblical territories due to the continuous international conflicts and fratricidal struggles, make this photographic collection a set with a very high patrimonial value.

Father Romuald Díaz describes this photographic collection in the biography of Father Ubach as follows:

«Let us say here something of the photographic archive of the Bible and its arrangement, as conceived and left by Father Ubach. Most of the photographs are his work, in a total number of more than eight thousand. All the clichés are numbered and grouped in the hundreds, each with the corresponding legend. How can one use that material to illustrate a biblical passage among so many thousands of photographs? To this end, Father Ubach drew up a triple catalog based on ballots:

- – Catalog according to the books, chapters and verses of Sacred Scripture, in which the file numbers of the corresponding photographs are carefully noted in each place.

- – Catalog where the names of cities, towns, mountains, rivers and other geographical places in Palestine and other biblical countries, from which one or more photographs have been obtained, are listed in alphabetical order.

- – Catalog with a certain distribution of subjects: folklore, archeology, Bedouins, Arabs, sedentary, Jews, shepherds, farmers, animals, plants, landscapes, wells, caves, etc.

I encara feu un altre treball per al maneig de l’arxiu.

And even if I do other work to manage the file. In order to better control the material available for the illustration of a specific verse of Holy Scripture, he had the patience to make a map of Palestine, distributed on cardboard. On each cardboard or map fragment the places mentioned in the Bible are noted with a simple order number; the number corresponds to a separate sheet, where the documentation referring to the place can be found: description of the place according to different authors; if he has been personally visited by Father Ubach, and references of date and photos taken; observations in the event that it has not yet been visited, and what are the particularities that should be taken into account on the day of the visit; information that has been obtained or that has been asked of the local people about a point to be clarified, etc. Thus, when the occasion came for an excursion through a certain area, it was not necessary for Father Ubach, but to take the map, look at the numbers of the places included in the itinerary and check the respective specifications. In a few moments he saw everything that would have to be kept in mind in the course of the trip, in order to get the most out of it. Once the excursion was done, he kept writing down, at least schematically, how long it had lasted; if he had performed it in company or alone-in the latter case he never forgot to say that he had done it in the company of the guardian angel-; if he had gone by donkey or camel, on foot or by car; what had been the itinerary followed; if it was for a scientific purpose or to please a friend; annotation of the photographs obtained and, finally, how much he had spent. The diagrams mentioned were a quick guide that served to guide him in everything related to the Illustration of the Bible» (Díaz Carbonell, 1962, p. 221-222).

Father Ubach, when he made the trip to Sinai in 1913, probably used a Kodak 3 camera, Folding Pocket, with celluloid film. These cameras appeared from 1908 onwards and were modified and improved over the years.

Later, around 1925, his collaborators, led by Fr. Benet Junqué, used a Contessa Nettel Deckullo camera. It was a machine for making negatives with a glass plate, although with the purchase of an accessory, it could make celluloid negatives

The work of Ubach and his collaborators is documentary photography conceived to illustrate the Great Bible of Montserrat. Their visual choices follow the dictates of the text, so when they have to capture the landscapes or monuments of the story, they do so by accentuating their timelessness and disregarding any human presence or reducing it to a point of reference. In contrast, when they photograph characters or actions, their perspective is more modern and empathetic towards the local people, paying attention to clothing, as well as to their gestures in ceremonies or the way they work. They focus on those segments of society that interest them in order to illustrate the biblical story and disregard the rest. They photograph the rural world much more than the urban, inland areas more than coastal zones, and Christian and Muslim communities more than Jewish ones. At the same time, they ignore everything related to modernity and its innovations and overlook the anti-colonial movements or the tensions and conflicts stirred up by the growing Jewish emigration.

To accentuate the drama, they reinforce the contrast between the different planes of the scene and contrast the smallness of the human figure with the immensity of the landscape. The desire to monumentalize the natural scenery finds its full expression in the use of panoramic views, which are constructed by overlapping snapshots taken from the same axis of rotation.

There is a desire for humanization that is manifested in the incorporation of the inhabitants of the ruins, guides or children who act as such, in order to establish a contrast between past and present that alleviates the severity of heritage elements.

The urban life of the Middle East, and especially that of Jerusalem, is shown by emphasizing what makes it unique: its cultural diversity. The images present either individuals from different communities interacting with each other, or homogeneous groups -often family- belonging to ethnic or religious minorities, or daily, festive or leisure activities that take place in emblematic places for a different community.

The interest in the Arab peasantry lies in the closeness we see between their way of life and the practices described in the biblical texts. For this reason, his camera offers a deliberately archaic vision, which emphasizes the most ancestral aspects of the daily life of farmers in the area.

The Bedouins are the group to which most attention is devoted, because in them they believe that he would have lived continuously in that territory since biblical times. In his photographs of men, he expresses dignity and a certain romantic drama, which is reinforced by contrasting the loneliness of the individual with an extremely hostile environment. At the same time, when women and children are portrayed, they do so with strong empathy, seeking closeness and attention to the details of gestures and bodywork.

The public expression of religiosity through festive celebrations and collective rites of the different communities that inhabit the Middle East allows to illustrate practices already described in the biblical texts, reaffirming the impression of a real or imagined community with respect to ‘that remote past.

Knowledge of the different Arab Christian communities, their liturgy and their social uses are one of the topics that interest them most. However, they never miss the opportunity to pass other minority groups (Jews, Yazidis, …) in front of their camera, but always out of respect and the most genuine curiosity.

Bonaventura Ubach gives us graphic testimony of a rapidly changing Middle East.

The fragile, often tense stability of Ottoman Palestine broke down with the emergence of modernity in the wake of World War I, European colonialism, and the consolidation of mutually exclusive and conflicting national projects.

The society shown in these photographs no longer exists. The cultural and religious diversity of that society has given way to a far more compartmentalised and culturally homogeneous world, less prone to the mutual knowledge and peaceful coexistence so valued by the Montserrat biblical scholar.

La Bíblia. Traducció dels textos originals i comentari pels monjos de Montserrat. Montserrat: Monestir de Montserrat. 1926-1982. 25 volums.

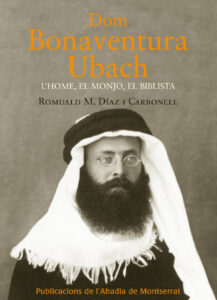

Díaz Carbonell, Romuald M. (1962). Dom Bonaventura Ubach: l’home, el monjo, el biblista. Barcelona: Aedos. Reeditat el 2012 per Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

Díaz Carbonell, Romuald M. (1962). Dom Bonaventura Ubach: l’home, el monjo, el biblista. Barcelona: Aedos. Reeditat el 2012 per Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

Díaz Carbonell, Romuald M. (1985).“Presència de Terra Santa a Montserrat (I)”. Dins: Montserrat: butlletí del Santuari, Núm. 12, p. 39-44.

Díaz Carbonell, Romuald M. (1986).“Presència de Terra Santa a Montserrat (II)”. Dins: Montserrat: butlletí del Santuari, Núm. 14, p. 37-44.

Díaz Carbonell, Romuald M. (1986).“Presència de Terra Santa a Montserrat (III)”. Dins: Montserrat: butlletí del Santuari, Núm.15, p. 28-34.

Donoso Matthews, Tatiana (2012) Fons fotogràfic el Pare Ubach: pla de gestió integral per a la seva valoració i activació patrimonial. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. Màster en Gestió del Patrimoni Cultural.

Giralt i Balagueró, Josep; Molist i Montaña, Miquel [eds.]. Viatge a l’orient bíblic = A Journey to the land of the Bible (2011). Barcelona: Institut Europeu de la Mediterrània: Museu de Montserrat: Museu d’Història de Barcelona.

Massot i Muntaner, Josep (1979). Els creadors del Montserrat modern: cent anys de servei a la cultura catalana. Barcelona: Publicacions de l’ Abadia de Montserrat.

Ubach, Bonaventura (1913). El Sinaí: viatge per l’Aràbia pètria cercant les petjades d’Israel (2 abril-8 maig, 1910). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Oliva impresor.

Ubach, Bonaventura (1913). El Sinaí: viatge per l’Aràbia pètria cercant les petjades d’Israel (2 abril-8 maig, 1910). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Oliva impresor.

Ubach, Bonaventura (1955). El Sinaí: viatge per l’Aràbia pètria cercant les petjades d’Israel (2 abril-8 maig, 1910). Barcelona: Abadia de Montserrat.

Ubach, Bonaventura (2011). El Sinaí: viatge per l’Aràbia pètria cercant les petjades d’Israel (2 abril-8 maig, 1910). Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

Ubach, Bonaventura (2009). Dietari d’un viatge per les regions de l’Iraq (1922-1923). Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

Tel.: 938 77 77 68

E-mail: biblioteca@abadiamontserrat.net

Adress: Abadia de Montserrat, Biblioteca

08199 Montserrat – Barcelona